By: Cody Gramlich, Physiotherapist

Most of us have been there before. You go to pick something up off of the floor and there it is. Back pain so severe you feel like you may never be able to walk again. An alternative scenario is pain that won’t stop nagging throughout your workday. You could also be someone who notices a ‘twinge’ every time you attempt a back squat.  Regardless of the situation, a LOT of people experience back pain. If you haven’t, you are one of the lucky ones in the minority. The good news is, with proper understanding and management, it doesn’t have to define you! If any of this sounds familiar to you, the information below will be of benefit. You will gain a better understanding of back pain, how to manage it, and how to prevent it.

Regardless of the situation, a LOT of people experience back pain. If you haven’t, you are one of the lucky ones in the minority. The good news is, with proper understanding and management, it doesn’t have to define you! If any of this sounds familiar to you, the information below will be of benefit. You will gain a better understanding of back pain, how to manage it, and how to prevent it.

What is Mechanical Low Back Pain?

Starting with a very general overview of the anatomy of the lumbar spine (low back), it consists of 5 vertebrae, separated by intervertebral discs. The vertebrae provide structural support, guide movement, and provide protection for your spinal cord and spinal nerves. Your intervertebral discs provide shock absorption from impact activity and bending. Your lumbar spine also has various ligaments and muscles that contribute to structural support and movement. As you can see in the second image below, there is close interaction between the areas above and below your spine due to the overlap of multiple ligaments and muscles. These muscles help facilitate movement of your low back in 3 different planes:

- Flexion/extension (forward/backward)

- Lateral flexion (side bending)

- Rotation (twisting)

Mechanical low back pain (also referred to as non-specific low back pain) is defined as “low back pain not attributed to recognizable, known specific pathology”3. As the name and definition suggest, you cannot conclusively determine the structure at fault for mechanical low back pain. Many research studies have indicated that even imaging (x-ray, CT scan, MRI) does not always correlate with clinical findings when it comes to low back pain. To hammer this point home, one of my mentors and colleagues used to say, “we could sit down and drink a few pitchers of beer arguing what we think the specific cause of mechanical low back pain is”.

When your low back pain is being assessed, the first step is to rule out any  specific/serious causes of your pain. Examples of this include, but are not limited to, radiculopathy (nerve related deficits), cauda equina syndrome, tumor, fracture, infection, and inflammatory disease. If these more specific causes are ruled out, it is then labelled as non-specific mechanical low back pain. You may be asking yourself “how can a physiotherapist help if they cannot identify the cause of my back pain?”. The goal of assessment/treatment with a physiotherapist will be to manage the symptoms and identify contributing factors that may have led to the development of it in the first place.

specific/serious causes of your pain. Examples of this include, but are not limited to, radiculopathy (nerve related deficits), cauda equina syndrome, tumor, fracture, infection, and inflammatory disease. If these more specific causes are ruled out, it is then labelled as non-specific mechanical low back pain. You may be asking yourself “how can a physiotherapist help if they cannot identify the cause of my back pain?”. The goal of assessment/treatment with a physiotherapist will be to manage the symptoms and identify contributing factors that may have led to the development of it in the first place.

Potential contributing factors to the development of your low back pain3,4:

- History of trauma

- Strain or overuse

– Postural dysfunction

– Dysfunction above and below the low back (mid back, pelvic girdle, hips)

– Core weakness or muscle imbalances

– Psychological factors (ex. fear of movement, depression)

– Work environment

– Pregnancy

Since mechanical low back pain is so common, there has been a significant amount of research surrounding it, producing clinical practice guidelines (best practices) for diagnosis and management. A stratified approach is now most commonly suggested. The recommendations for management of your low back pain will differ depending on what group or subgroup you are categorized into. These groups/subgroups are usually based on chronicity of your back pain (acute, sub-acute, chronic) and presence of external factors that may contribute to it (psychological, work environment, etc.)1,3,4,6.

Why is it Important to Understand Mechanical Low Back Pain?

Low back pain affects 60-80% of individuals at some point in their lifetime3. Of these  people, over 90% that present to a primary care practitioner have non-specific mechanical low back pain4. Back pain is also a significant economic burden to society. It is reported that the cost of care for low back pain is $50 billion annually in the United States4. Up to 23% of the world’s adults suffer from chronic low back pain (lasting longer than 3 months), which requires significant health care costs3. Without diving too deep into politics, in Canada’s public health care system and considering the significant costs associated with back pain, you could certainly argue it affects us all.

people, over 90% that present to a primary care practitioner have non-specific mechanical low back pain4. Back pain is also a significant economic burden to society. It is reported that the cost of care for low back pain is $50 billion annually in the United States4. Up to 23% of the world’s adults suffer from chronic low back pain (lasting longer than 3 months), which requires significant health care costs3. Without diving too deep into politics, in Canada’s public health care system and considering the significant costs associated with back pain, you could certainly argue it affects us all.

It is important to note that low back pain tends to be a self-limiting condition. Half of individuals will recover from it in 2 weeks without treatment, and the majority of individuals will recover in 1-4 months without treatment4. Although this is true, the recurrence rate of low back pain is high. 60% of people are likely to experience another episode of low back pain within 3-6 months4. These statistics indicate why it is important to see a rehab professional. First, some guidance will give you a higher likelihood of recovering in a shorter time frame. Second, education on your back pain will allow you to take preventative steps to decrease the likelihood of recurrent episodes.

As mentioned earlier, current guidelines take a stratified approach to diagnosing and treating mechanical low back pain. Depending on where you are categorized, the  treatment may differ slightly. However, within each category, a few common themes exist. First, one of the most important aspects of care is providing reassurance and education. The better you understand your low back pain, the better you will be equipped physically and psychologically to deal with the pain. Second, exercise therapy and maintaining an active lifestyle is a key component to preventing and managing it. When it comes to mechanical low back pain, as long as a primary care practitioner has ruled out red flags, it is safe to move, and encouraged to help recovery. Finally, a multidisciplinary approach to low back pain management is recommended. This could include (but is not limited to) pharmaceuticals, psychology, conservative care, and self management1,2,4,5.

treatment may differ slightly. However, within each category, a few common themes exist. First, one of the most important aspects of care is providing reassurance and education. The better you understand your low back pain, the better you will be equipped physically and psychologically to deal with the pain. Second, exercise therapy and maintaining an active lifestyle is a key component to preventing and managing it. When it comes to mechanical low back pain, as long as a primary care practitioner has ruled out red flags, it is safe to move, and encouraged to help recovery. Finally, a multidisciplinary approach to low back pain management is recommended. This could include (but is not limited to) pharmaceuticals, psychology, conservative care, and self management1,2,4,5.

Some Risk Factors for Developing Mechanical Low Back Pain4:

– Standing or walking > 2 hours per day

– Frequent moving or lifting > 25lbs

– Increased driving time (occupational)

– Limping or altered gait

– Obesity

– Psychosocial factors (income level, stress level, poor relationships at work)

– Prior low back pain

– Posture

– Poor muscular endurance (low back and core)

How Do I Know If I Have Mechanical Low Back Pain?

– Pain, ache, or stiffness in the lumbosacral region (small of your back)

– Pain may radiate into your buttocks or upper leg (more often one sided)

– Pain may radiate into your buttocks or upper leg (more often one sided)

– Pain may come on due to a specific event (bend, lift) or insidiously (gradual, no cause)

– Pain will increase or decrease with positional changes, certain movements, or lifting

– NO signs of Red Flags (i.e. significant trauma, unexplained weight loss, widespread neurological issues)

– NO known specific pathology (i.e. fracture, infection)

*Remember that these are the most common symptoms that would indicate you may have mechanical low back pain. It may present with different signs/symptoms depending on the individual. If this sounds like you, reach out to a physiotherapist or another health care practitioner for a thorough assessment to determine the cause of your specific symptoms.

3 Strategies to Help Manage Your Mechanical Low Back Pain Symptoms

1. Keep it Moving

*Movement and activity are a key component to recovery and prevention of mechanical low back pain. Pick an activity you like to do (yoga, walking, cycling) and do it within the limits of your pain levels. You may have to modify the activity in the short term, but the movement will be beneficial for your body.

2. Low Back Mobility

*Working on mobility in your lumbar spine will help decrease pain levels and encourage more efficient movement in the long term. Try 3 sets of 10-15 repetitions.

3. Back/Core Strengthening and Motor Control

*Strength and coordination of the back, hip, and core muscles will allow you to get back to normal activity sooner and prevent episodes of back pain in the future. Try 3 sets of 8-10 repetitions on each side.

FAQ

How Do I Relieve My Low Back Pain?

It is best that you take an active approach or incorporate movement to help alleviate your back pain. Another suggestion includes using heat or ice to help decrease pain or muscle spasm. Clinical practice guidelines also recommend short term use of over-the-counter anti-inflammatory medications. However, it is best to consult a physician or pharmacist prior to use to ensure medication is safe and effective for you.

When Should I Be Worried About My Low Back Pain?

If your low back pain is non-specific mechanical low back pain, there is no need to be worried, as your pain will likely resolve with multimodal treatment. Mechanical low back pain is self-limiting, and it is usually safe to resume activity as tolerated. However, it is best to have it assessed by a physiotherapist or another health care professional in order to rule out red flags or specific causes of your pain that may require more immediate attention.

How Should I Sleep With Low Back Pain?

Most comfortable sleeping position will vary from person to person and there is no right or wrong answer. You may have to try a few different positions to find out what is best for you. One option to try is sleeping on your back with a pillow supporting your knees. Another option is sleeping on your side with a pillow between your legs. These options can put your pelvis and low back in a position that may relieve some discomfort.

What Comes Next?

Remember, mechanical low back pain is not attributable to any recognizable or specific pathology. It is one of the most common complaints to primary care practitioners and has a large burden on the health care system. Mechanical low back pain can be complex and multifactorial. It usually requires individualized management using a stratified approach. Education, an active lifestyle, and multidisciplinary management will aid in more successful outcomes.

Start by trying some of the strategies listed above and see how it goes! Afterwards, it would benefit you to see a physiotherapist to guide you through treatment, depending on your response.

Feel free to reach out if you have any additional questions on mechanical low back pain, or you can book an appointment online by clicking here.

References:

- Almeida, M., Saragiotto, B., Richards, B., & Maher, C. G. (2018). “Primary care management of non-specific low back pain: key messages from recent clinical guidelines”. The Medical Journal of Australia, 208(6), 272–275. doi:10.5694/mja17.01152

- Oliveira, C.B., Maher, C.G., Pinto, R.Z. et al. “Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: an updated overview”. European Spine Journal 27, 2791–2803 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-018-5673-2

- Physiopedia 2021. “Low Back Pain”. Physiopedia. Accessed March 16, 2021, https://www.physio-pedia.com/Low_Back_Pain

- Physiopedia 2021. “Non Specific Low Back Pain”. Physiopedia. Accessed March 16, 2021, https://www.physio-pedia.com/Non_Specific_Low_Back_Pain

- Qaseem, A., Wilt, T.J., McLean, R.M., et al. “Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine. (2017) ;166:514-530. [Epub ahead of print 14 February 2017]. doi:10.7326/M16-2367

- Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy (2013). “KNGF Guideline: Low Back Pain”. Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap voor Fysiotherapie, KNGF. http://www.ipts.org.il/_Uploads/dbsAttachedFiles/low_back_pain_practice_guidelines_2013.pdf

Media References:

Anatomy Pictures:

- Click Physiotherapy (N.D.). “Lower Back Pain: Exercises and Stretches”. Accessed March 19, 2021 via Google Image Search. https://clickphysiotherapy.blogspot.com/2019/01/lower-back-pain-exercises-and-stretches.html [Original Source Unknown]

the bus, going up stairs at the office, or squatting to pick up your child. This hits close to home for me, as this was similar to what I was experiencing when I developed knee pain two months prior to running my first half marathon. With proper activity modification and management of the injury, I was able to complete the half marathon as planned! In this blog, you will learn about the presentation and management of one of the most common types of knee pain, patellofemoral pain syndrome.

the bus, going up stairs at the office, or squatting to pick up your child. This hits close to home for me, as this was similar to what I was experiencing when I developed knee pain two months prior to running my first half marathon. With proper activity modification and management of the injury, I was able to complete the half marathon as planned! In this blog, you will learn about the presentation and management of one of the most common types of knee pain, patellofemoral pain syndrome.

especially for those of you who are runners. It is estimated to have an incidence of 3-15% in active populations and a prevalence of up to 23% in the general population3,4. In my personal caseload, I have treated this condition numerous times, both in adolescents and adults.

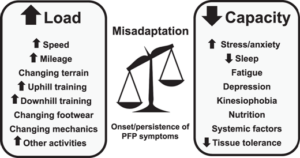

especially for those of you who are runners. It is estimated to have an incidence of 3-15% in active populations and a prevalence of up to 23% in the general population3,4. In my personal caseload, I have treated this condition numerous times, both in adolescents and adults. there are many contributing factors to the onset of the pain in the first place1,2. This should include education on taping and footwear. This should include managing beliefs/expectations on recovery. This should also include education on load/capacity, exercise, and run re-training1. A physiotherapist will be able to support you in most of these areas to give you an opportunity to get back to doing what you love.

there are many contributing factors to the onset of the pain in the first place1,2. This should include education on taping and footwear. This should include managing beliefs/expectations on recovery. This should also include education on load/capacity, exercise, and run re-training1. A physiotherapist will be able to support you in most of these areas to give you an opportunity to get back to doing what you love.

reach to grab a plate from the cupboard, or you can’t roll over at night to sleep on your side. This is what one client was struggling with before choosing to start physiotherapy. With a better understanding of his issue and how to manage it, he was able to return to playing pickleball up to five times per week without shoulder pain! One common cause of shoulder pain is commonly referred to as subacromial impingement, or subacromial pain syndrome. In this blog, you will learn what subacromial pain syndrome is, why it is important to understand, and what you can do to manage it.

reach to grab a plate from the cupboard, or you can’t roll over at night to sleep on your side. This is what one client was struggling with before choosing to start physiotherapy. With a better understanding of his issue and how to manage it, he was able to return to playing pickleball up to five times per week without shoulder pain! One common cause of shoulder pain is commonly referred to as subacromial impingement, or subacromial pain syndrome. In this blog, you will learn what subacromial pain syndrome is, why it is important to understand, and what you can do to manage it.

Shoulder pain is common and can result in significant loss of function or participation in your day-to-day activities. It is suggested that up to 67% of community dwelling individuals may experience shoulder pain1. 44-65% of all reports of shoulder pain are thought to involve symptoms arising from the subacromial space1. Subacromial pain syndrome is a prevalent issue, so it is important to understand how to prevent and manage it.

Shoulder pain is common and can result in significant loss of function or participation in your day-to-day activities. It is suggested that up to 67% of community dwelling individuals may experience shoulder pain1. 44-65% of all reports of shoulder pain are thought to involve symptoms arising from the subacromial space1. Subacromial pain syndrome is a prevalent issue, so it is important to understand how to prevent and manage it. as the first-line treatment in subacromial pain syndrome6. A strong recommendation to include manual therapy as an integrated treatment was also made6. Another systematic review even suggested exercise to be as effective as arthroscopic surgery for subacromial pain syndrome3.

as the first-line treatment in subacromial pain syndrome6. A strong recommendation to include manual therapy as an integrated treatment was also made6. Another systematic review even suggested exercise to be as effective as arthroscopic surgery for subacromial pain syndrome3.